How the Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet were Discovered

Posted by Phil Heler on February 21, 2024The food on the end of your fork is one of the most important factors in determining your health. This may sound obvious today, but seventy years ago this idea was met with a great deal of scepticism until the work of Ancel and Margaret Keys.

The food on the end of your fork is one of the most important factors in determining your health. This may sound obvious today, but seventy years ago this idea met with a great deal of scepticism.

The influence of diet on cardiovascular disease was widely doubted. The conventional medical wisdom of the day, no matter how much cheesecake you ate, was that cardiovascular disease was the inevitable consequence of aging.

However, the pioneering work of Ancel and Margaret Keys challenged this popular misconception. Their hugely influential epidemiological studies and three books Eat Well & Stay Well (1959), How to Eat Well and Stay Well the Mediterranean Way (1975) helped reverse opinions of the day.

Their work remains both seminal and entirely relevant today. Their recommendations are still thoroughly valid and endorsed by all current guidelines.

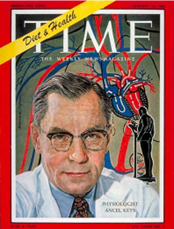

Ancel Keys was one of the most remarkable characters of his time. He was born in humble surroundings in 1904 to teenage parents in California. His life would go on to be full of adventure and discovery.

Indeed, his early life reads like a ‘Boy’s Own’ adventure manual. This young unsuspecting teenager would have been bewildered if he had realised he would end up on the cover of ‘Time’ magazine on January 13th 1961.

As a teenager he worked in the wilderness in lumber camps and then as a ‘powder monkey’ in goldmines in New Mexico. He then also helped extract guano (or bat poo) in Sierra Nevada.

Guano was seen as especially valuable as a rich source of nitrates and phosphates (great fertiliser). He worked on a steamship that sailed to China and there he learned Chinese.

He came back home and then bizarrely worked at Woolworth’s where in his own words ‘the work soon became intolerably dull’. Then he started his academic career.

He obtained his MSc and PhD in Berkeley in 1928 and 1930 respectively in biology. After that, he specialised in physiology by pursuing a PhD at Cambridge, which he received in 1936.

He met his wife Margaret, a biochemist, and married her in 1939. At this point he undertook pioneering studies on the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood.

He organised a high-altitude expedition to South America and spent 6 months on the slopes of the Andes. Here he experimented on himself spending ten harrowing days above 20,000 feet to observe and measure the effects of altitude on his own blood.

But it was the Second World War that really galvanised interest. The husband-and-wife team realised that as food supplies dwindled in post-conflict Northern Europe the mortality rates of heart disease fell significantly.

This was related to a reduction in consumption of high fat foods such as dairy products and meats. Meanwhile exactly the opposite was happening in the U.S. where there was an increase in heart disease. Theoretically if some countries had much lower rates of heart disease this indicated the potential for population-level prevention.

This culminated in the genesis of one of their first ever studies into cardiovascular disease in 1947 called ‘The Minnesota Business and Professional Men’s Study’.

Together they recruited 281 local businessmen between 45-55 years old and submitted them to examinations every two years for 15 years to assess their cardiovascular health.

They recorded weight, blood pressure, ECG results, and cholesterol levels. Of the participants 32 men suffered from a heart attack (or myocardial infarction or MI).

They concluded that the only significant predictor of a heart attack was a high total cholesterol level. Naturally the conclusions came under harsh criticism from commercial interests such as the meat and dairy industry.

Building on this evidence, the couple travelled the world to study the diets of different countries and devised a study. Arguably their most important scientific achievement was launched in 1957 called the ‘Seven Seas Study’.

The study surveyed 12,000 healthy middle-aged men aged 40 to 59 living in Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, the Netherlands, Finland, Japan, and the United States. Communities were selected because of their contrasting dietary patterns. They were also selected because they were uniformly rural labouring populations.

They analysed what foods randomly selected families ate. They were able to determine when saturated fats were a key component of any given meal (typical in Finland and the U.S).

This was correlated to cholesterol levels and heart disease. They noticed in cultures where diets were based on fresh fruit and vegetables, bread, pasta, and a lot of olive oil (e.g. the Mediterranean region) blood cholesterol was low and heart disease was rare.

The report published in 1970 had a decisive impact on cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention. It was one of the first studies to clearly demonstrate that dietary saturated fat leads to high levels of CVD. This has since been proven consistently time and time again in subsequent investigations.

The evidence has endured and the Mediterranean diet — rich in fruits, vegetables, pasta, and olive oil, with small portions of meat, fish, and dairy products — has certainly become a reference diet.

In 2020 a comprehensive review in the well-respected Journal of Internal Medicine confirmed the benefits of the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) and linked it to good cardiovascular health. They concluded that the diet led to a reduction in obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome (refer below) and dyslipidaemia (too many fats in your blood).

They also suggested that the MedDiet is associated with lower rates of incident diabetes. It was also associated with less age-related cognitive dysfunction and lower incidence of neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Alzheimer’s disease.

To give even further validation, the Mediterranean diet was given UNESCO status in 2013 by being included on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

UNESCO is of course the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Their description of the MedDiet is wonderful. It brings to life a system of eating, community and social interaction which is fast disappearing in the UK.

‘Involving a set of skills, knowledge, rituals, symbols and traditions concerning crops, harvesting, fishing, animal husbandry, conservation, processing, cooking, and particularly the sharing and consumption of food’.

‘Eating together is the foundation of the cultural identity and continuity of communities throughout the Mediterranean basin. It is a moment of social exchange and communication, an affirmation and renewal of family, group or community identity’.

It is just worth mentioning one last thing. During their work, Ancel and Margaret noticed something. In one of their study areas – in southern Italy – there were a surprisingly large number of centenarians.

The pair was so convinced by the local diet as the key to this longevity that they relocated there when they retired. Ancel died in 2004 aged 100 and Margaret died aged 97. This just seems to add further credence to their message.