A New Way of Looking at the Food We Eat

Posted by Phil Heler on April 7, 2024There is a very convincing argument that nutritional guidelines in the UK are long out of date. On average, we are told women should have around 2000 calories a day and men around 2,500. But are all calories equal?

There is a very convincing argument that nutritional guidelines in the UK are long out of date. On average, we are told women should have around 2000 calories a day and men around 2,500. But are all calories equal?

Is a calorie from highly refined sugar of equal value to a calorie of a carbohydrate locked inside the cellular structure of a whole food? We rapidly absorb highly refined sugar.

The whole food is slowly absorbed as we break down cell walls with our digestive enzymes; the fibre allows us to feel satiated and suppresses the urge to raid the biscuit barrel. Furthermore, each of us has different rates of metabolism meaning that some of us burn calories more rapidly than others.

Then there is the issue of counting calories which is challenging.

We can all get carried away. The director Orson Wells, famous for his overindulgence, once said; ‘My doctor told me to stop having intimate dinners for four. Unless there are three other people.’

Calories can come from good or bad food. The concept does not consider the connection between obesity and ultra processed food (UPF) consumption. According to a government National Diet and Nutrition Survey in 2023 75% of calories in the school lunches of secondary school children came from UPFs. Is it any wonder that since 2019, for the first time in a generation, life expectancy has actually decreased by 38 weeks? But it isn’t all bad news.

It would appear in the UK that the government strapline of eating your five-a-day has slowly been adopted. Ironically, even though our waistlines are gently expanding we can at least now boast that we come first for eating our fruit and veg. According to a survey in 2023 by OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) the UK and Ireland top the tables for fruit and vegetable consumption.

One in three of us now consume five or more portions of fruit and vegetables a day which is more than any member country with OECD membership. While this is indeed a good thing, does the simple recommendation of five-a-day go far enough? After all an iceberg lettuce (that has a shelf life that is longer than a Prime Minster) may count toward your five-a-day but it is devoid of any polyphenols.

These plant chemicals are really good for our health because they encourage the growth of good bacteria in our microbiome. Polyphenols also need to be derived from a wide variety of plant-based foods.

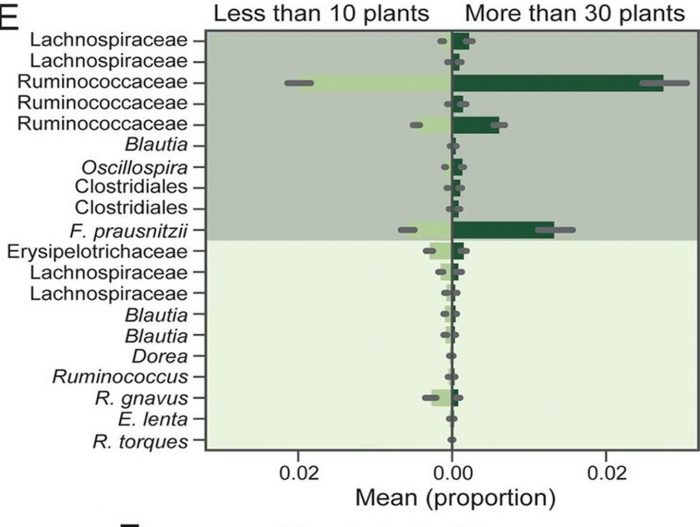

Current research suggests that we need to eat at least 30 different plants a week to optimise our gut health. Our gut health is perhaps more significant than we realise. We each of us share 99% of the same DNA, however our gut microbiome varies enormously, independently of genetics. The ZOE PREDICT 1 study demonstrated that even genetically identical twins have very different gut microbiomes.

Unrelated individuals only share roughly 30% similarity in the species of bacteria in their microbiome and twins meanwhile are only slightly better at 34%. Each of us has a unique set of bacteria. Clearly, we cannot change our genetics, but we can modify our gut microbiome to promote better health outcomes.

This makes it an obvious candidate for targeted nutrition. The gut microbiome is basically a massive chemical factory, much of which interacts with our immune system, metabolism and central nervous system.

A large research project published in 2019 called the British and American Gut Project looked at the diet of thousands of people. This study was the first large investigation to look at poo samples on a massive scale and the diversity of bacteria within it. Over ten thousand poo samples (that’s a lot of poo) were taken from people in America, UK and Australia. These were analysed and then related back to their diet.

One of the key findings was that the greater the number of unique plants someone ate, the wider the microbial diversity in their gut biome irrespective of whether they were vegan or omnivore. The greater the microbial diversity, the more robust, the bigger the chemical factory which resulted in better health.

The results also demonstrated some very interesting findings regarding fibre intake. Fibre intake as we know is good for us but for our gut microbiome it is an amazing fertilizer.

In 2019 a review on fibre intake, published in The Lancet, looked at 260 studies and clinical trials involving roughly 5000 participants. When they number-crunched all the data there were some very clear patterns.

The health benefits conferred by eating at least 25g of fibre a day led to a 15–30% decrease in all non-communicable diseases when compared with consumers who had low dietary fibre intakes. Clinical trials showed significantly lower body weight, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol when comparing higher with lower intakes of dietary fibre. However, there was something missing.

These studies did not comment on the significance of the variety of fibre intake which is probably more important than the overall quantity. The British and American Gut Project proved that eating more plants diversifies the types of fibre you eat.

This has a beneficial effect on the gut microbiome because you are consuming a wide variety of what are great party foods for your bacteria. Of the 10,000 people in the study who ate the largest variety of plant foods, they were found to have the healthiest microbiomes and better health outcomes over time.

The study suggested that 30 was the optimum number of different plants for fibre diversity, as there wasn’t much improvement when you increased from 30 to 35 or 40.

Our perception of food has evolved to be very simplistic because this is what the guidelines tell us. The guidelines look at macronutrients such as fat, protein and carbohydrate and of course vitamins. We have all spent small fortunes on vitamin supplements that we do not need.

Foods have become known for just one thing. Take an orange for example. We associate it with just Vitamin C. This is all down to British naval surgeon James Lind. In 1747 he selected 12 men from HMS Salisbury, all suffering from the condition scurvy and through trial and error discovered that citrus fruit reversed the condition.

Yet vitamin C (or ascorbic acid) is just one of many polyphenols found in citrus fruits. Its importance seemingly eclipses the relevance of other amazing polyphenols such as hesperidin, another important chemical in citrus fruits.

The reality is that an orange contains several thousand chemical compounds. These include at least 60 different types of chemical structures that contribute to flavour. There are 57 different compounds called flavonoids (hesperidin is one) which are the most common type of polyphenol.

A blood (or blush) orange for example has five times the antioxidative capacity of a normal orange making it the superstar of the citrus family. This is nothing to do with vitamin C content as it contains the same amount as other types of oranges.

It is the concentration of flavonoids called hesperidin, narirutin and naringin that give it its potency. Polyphenols are great for our health. There is even a plausible case for polyphenol content to be declared on food labelling because it really does matter. But this is the problem with labelling. Foods are too nuanced and complex. It is impossible to condense their attributes into just a simple list.

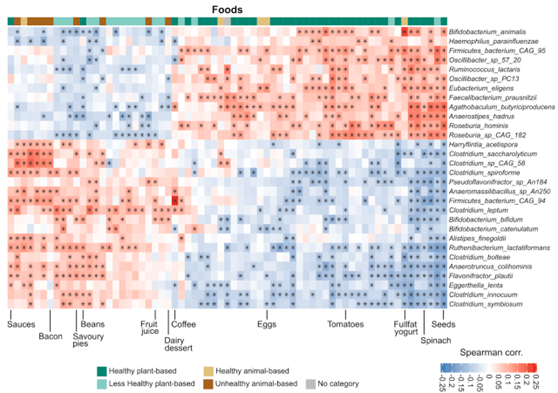

The diagram below from the ZOE PREDICT study gives some idea of the effect of healthy plant-based foods rich in polyphenols versus animal-based foods rich in saturated fat with no polyphenols on microbiome diversity. We can see that bacon and pies perform poorly and have a negative effect while yoghurt and spinach are at the other end of the spectrum.

In the last 20 years epidemiological studies strongly suggest that long term consumption of diets rich in plant polyphenols offer a good health benefit. They help generate protection against development of cancers, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, osteoporosis and neurodegenerative diseases. They also have a positive effect on our digestion and overall gut health by stimulating the growth of health promoting bacteria, like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. At the same time it is thought they help inhibit the growth of detrimental and possibly harmful bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Clostridium perfringens, and Helicobacter pylori.

As always, the bottom line is to choose fresh, whole foods as much as possible, and to eat a wide variety of colourful (and tasty) foods. By including fewer ultra-processed foods, you can reduce disease risk and promote your health.