Spinal Discectomy & Herniated or Prolapsed Discs

Posted by Phil Heler on July 4, 2020Since we offered IDD Therapy as a possible non-invasive conservative alternative to surgery, we have often explained to patients the different surgical options that run alongside.

Currently I am covering the most common spinal surgeries and this week we are discussing discectomy surgery. This is something we have learned more and more about at the clinic over the last few years. Since we offered IDD Therapy as a possible non-invasive conservative alternative to surgery, we have often explained to patients the different surgical options that run alongside.

Patients are keen to exhaust conservative options before electing to have surgery but also naturally want to know what surgery involves. Sometimes even conservative measures such as IDD are unlikely to succeed and surgery may be a necessity. The most common reason for this is a large disc herniation (or prolapse or ‘slipped’ disc) or severe degenerative changes.

For severe degenerative changes two of the most common spinal surgeries are laminectomies and spinal fusions (which we wrote about last week). However, for large disc herniations or bulges another common procedure is a discectomy.

Clearly a discectomy is designed to provide relief from pressure exerted on exiting spinal nerves or on the spinal cord itself. A laminectomy can also be performed at the same time to help give access to the disc if required. Disc herniations are quite common and some estimates suggest that they can affect at least 40% of us at some point in our lives. They are most common reason for spinal surgery.

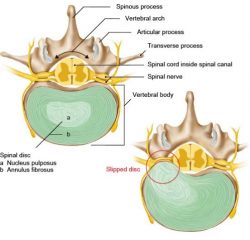

Just to be clear there are a few terms commonly used when describing discs which need clarifying. A disc bulge is where the outer wall of the disc (annulus fibrosus) bulges out from its normal position. The disc wall is not broken, and the soft material which acts like a fluid ball bearing (nucleus pulposus) remains inside the disc. As the disc bulges, it may press against nerves directly.

We see a lot of disc bulges in clinic and often these people may present with acute sciatica (pain down the leg) or pain in the lower back and buttock.

Herniated or Prolapsed Discs and Where They usually Occur

A herniated disc or prolapsed disc meanwhile is when the soft material in the nucleus of the disc herniates through the outer disc wall. Unfortunately, this usually happens in roughly the same place, typically at the point where the nerve roots exit the spinal cord. In this case the nucleus material presses directly on to the spinal nerve acting both as a space occupying lesion whilst also causing biochemical irritation. This can generate a lot of pain either in the lower back or intense pain into an arm if the herniation is in the neck.

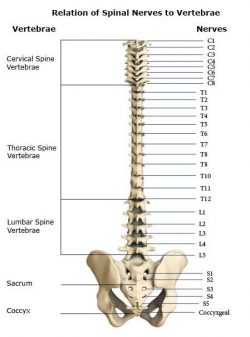

Each vertebra in the spine has numbers as you can see in the diagram above. In the lower back (or ‘lumbar spine’), the vertebrae are numbered L1 to L5.

The chest or ‘thoracic spine’ uses the letter T and is numbered T1-T12 and the neck or ‘cervical spine’ uses a C and is numbered C1-C7. Herniated or disc bulges usually occur in the same places. This is at the bottom your lower back at L3, L4 or L5 and at C4, C5, C6 and C7 at the bottom of the neck. In fact, degeneration in the spine is also chiefly focused at these levels and laminectomies and spinal fusions most often occur at these locations.

For the sake of completion there are also five rudimentary levels at the base of the spine in the sacrum (although these are fused vertebra) where nerves exit, and these are numbered S1-S5.

Surprisingly, a slipped disc does not always lead to noticeable symptoms. This has been demonstrated in studies in which adults who had no specifically obvious back pain were examined using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). More than 50 out of 100 of them had a bulging intervertebral disc. About 20 out of 100 had intervertebral discs that had herniated, again without causing any symptoms. For many of us who do have symptoms they will usually resolve over time. A few people are not quite so lucky.

When are Discectomies Usually Performed?

Discectomies are most often performed when disc herniations are clearly clinically significant, and swift action needs to be taken. Severe nerve impingement can cause weakness in the ankle when walking (known as foot drop) and progressive weakness in the leg. Progressive neurological symptoms and severe intractable pain are indicators for surgery.

In extreme cases loss of bowel or bladder control and tingling/ numbness in groin area indicates a possible medical emergency and in this case a discectomy is mandatory. This is called ‘cauda equina syndrome’ and it is important to remember that this is rare. In these rare cases a disc herniation is so large that it compresses the nerves (these are at S3) that supply that control the bowel and bladder.

The internal and external urethral sphincters (the valves that keep urine inside your bladder) start to lose function which results in these symptoms. If any of these symptoms are causing anyone who reads this article concern ring me at the clinic.

Open Discectomy and Microdiscectomy

The techniques that are generally used for discectomies are an open discectomy or microdiscectomy. These are the best surgical treatment options and are currently the most commonly used treatment modalities.

Open discectomy allows the surgeon the greatest ability to see and explore the site where the disc herniation is located and has therefore been ‘gold standard’. It is usually performed under general anaesthesia and typically requires a one-day hospital stay. It is performed with the person lying face down or in a kneeling position.

During the procedure, the surgeon makes approximately a one-inch incision in the skin over the affected area of the spine. Muscle tissue is removed from the bony arch at the back of the vertebra above and below the disc where there is an issue. Retractors hold the tissue away from the site of herniation (sorry if you are squeamish!), so the surgeon has a clear view of the vertebrae and disc.

For open surgery, the retraction of tissue is quite extensive, and this is a significant disadvantage as it damages spinal muscle and other tissues. In some cases, bone (as in a laminectomy) and ligaments may have to be removed for the surgeon to be able to visualize and then gain access to the disc without damaging the nerve tissue.

If required at this point, a spinal fusion can also be performed if there is spinal instability. At this point the surgeon will remove the section of the disc that is protruding from the disc wall and any other disc fragments that may have been expelled from the disc. The incision is then closed with sutures.

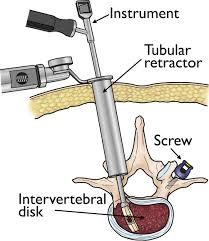

Microdiscectomies are a minimally invasive and use much smaller incisions compared to the standard open discectomy. A minimally invasive incision causes less disruption of the back muscles, helps decrease recovery time, has better cosmesis (i.e. cosmetically better) and may only require local anaesthesia. They may not always be relevant in every presentation. During these surgeries’ endoscopes are used, which are long thin flexible tubes that have a light and a camera at the end.

Another recent innovation is the type of retractors that are used to secure soft tissues. Tubular retractor systems such as the one above does not disturb anatomy in the way that older systems once did so this has been a significant innovation. This was first introduced in 1997 by Foley and Smith and then in 2003 they modified the tubular retractor to include a microscope hence the term ‘Micro Endoscopic Discectomy’ (MED) or ‘Micro Discectomy’.

According to some studies the risk of re-herniation after surgery varies from 3-24% but microdiscectomies have a lower ratio of side effects and research seems to indicate that the risk of re-operation has declined to 10% (Albayrak and Ozturk 2016). These two surgeons undertook microdiscectomies on 70 patients who had previously failed surgery between 2006-13 and required re-operations. These 70 patients were from a group of 1115 patients who had all had operations for disc herniations. After a seven year follow up all of these patients were still doing well.