Nutritional Values on Food Labelling are not as Accurate as you Think!

Posted by Phil Heler on February 15, 2022Put simply ‘we don’t eat nutrients - we eat food.’ Many of us clearly do rely on food labelling to give us information that helps determine our food choices. A food label will after all give us a simple list of nutrients. So, it must be right?

This week I am writing about why food labelling, despite best attempts, may not be as accurate as you think when it comes to listing the calorific value of basic nutrients.

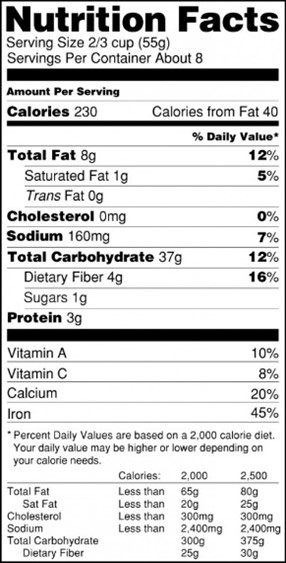

Of course, food labelling is strictly regulated, and no one is suggesting that it is deliberately misleading. It is more the case that it just needs revising having maintained a basic standard called the Atwater system for many years. This unambiguous system simply lists the basic ingredients as shown below. However as we will see food is much more complex.

Food Labelling & Branding

Product labelling and branding can cause headaches. In 2014 Colgate famously launched its toothpaste in France named ‘Cue’, without appreciating that it’s also the name of a French pornographic magazine. More embarrassingly Ford made an even bigger mistake in 1970 when marketing its new car, the Pinto in Brazil, because the term in Brazilian Portuguese meant ‘tiny male genitals.’

However, the overall prize must surely go to Perdue Farms. They are a $7 billion business and are one of (if not the) biggest chicken, turkey, and pork processing companies in the United States. Their founder Frank Perdue’s strap line was, ‘It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken.’ This was unfortunately accidentally translated into Spanish as ‘It takes a sexually stimulated man to make a chicken affectionate.’ And heads will roll.

It is always important to understand how claims or brands translate to or may be perceived in other languages or cultural contexts. In general, this is something that we are now much more aware of these days, even when it comes to naming new variants of COVID-19.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) deliberately avoided naming the newly named omicron variant ‘Xi’ for good reason (‘Xi’ precedes ‘Omicron’ in the Greek alphabet). This is because ‘Xi’ is the most common surname in China (760,000 Chinese have this surname). Also, the President of the People’s Republic of China is called Xi Jinping. He is one of the most powerful people in the world today, so don’t poke the bear. But back to food content labelling.

The Atwater system estimates the basic relative proportions of fat, carbohydrate, protein and fibre in each of the raw ingredients. This system has not been changed (partly because there are no viable alternatives) since it was invented by the American biochemist Wilbur Atwater in the 19th century. Historically even nutritional research has had a tendency just to focus on this list of simple nutritional information.

The basic nutrient values for food are extrapolated from huge food compositional databases worldwide such as EuroFir which is run by the European Food Safety Authority. In the UK the biggest database is held by Food Databanks National Capability (FDNC) which is based at the Quadram Institute in Norwich. Unfortunately, the truth is that the food we eat is much more complex than a simple list.

Put simply ‘we don’t eat nutrients – we eat food.’ Many of us clearly do rely on food labelling to give us information that helps determine our food choices. A food label will after all give us a simple list of nutrients. So, it must be right?

What is a Food Matrix?

This traditional labelling method is now being scrutinised as it does not tell us the whole story behind what we consume. Although in its infancy research is now focusing on what is known as the ‘food matrix’. This follows emerging science and strong evidence that indicates that there are factors at play, apart from a simple list of ingredients, that influence nutritional and health values of our food.

To illustrate this point here are a few examples. Cereal crops have historically always been a crucial long held dietary source of starch for us, particularly when it comes to energy. Yet how we process grains has great significance on bio-accessibility of the starch.

It makes sense that if you eat a bowl of porridge made from coarse-ground oats as opposed to finely ground oats there is a corresponding lower rise in your blood glucose levels, yet the list on the nutritional labelling would be identical. Equally there would be a defined physiological difference between eating whole nuts such as almonds compared to ground almonds. This simple change will alter the bioavailability of the fat and our body would respond in a very different way. This difference exists because of a change in the food matrix.

The best way to understand how we think of a food matrix is to look at food groups as different ‘tasty structures’ that have everything we need for energy, and to create and replace our tissues. One commentator neatly described the food matrix using the following description. ‘Molecules come embedded by nature in often complex functional microstructures that we cannot see, for example, inside cells as starch granules, or covered by a biological membrane as fat globules in milk.

During industrial food processing or cooking, we create new microstructures that further combine and hide food molecules due to mixing, shearing and heating. In food technology we call these special microstructural arrangements containing food molecules a food matrix.” (José Miguel Aguilera, Emeritus Professor of Chemical and Food Engineering at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.)

Research is gradually beginning to shift its focus to view the nutritional value of food as a function of its matrix. Fundamentally a food matrix will consider how the properties of whole foods influence the ability of our own bodies to break down and absorb the nutrients locked inside– and thereafter exactly what this means for our nutrition and health. Any one food will comprise a huge, complicated bewildering matrix of complex structures and compounds. All these properties will coalesce to create unique flavours, textures and tastes that we love (or abhor if you are my son and it’s broccoli).

How does a Matrix Influences Nutritional Value?

However, all these properties will also combine to radically change the nutritional value of any food. Any one food will have its own matrix. This can be a liquid (such as a juice), or an emulsion (like mayonnaise), or a fibrous matrix (any fruit or vegetables) or even a porous type of structure like a marshmallow.

Whole foods like fruit, vegetables, and grains, mean that our bodies must work harder by chewing, fermenting or dissolving structures such as cell walls within the food matrix to release nutrients. This means that nutrients are released and made available slowly over time. This influences our rate of digestion, insulin, blood glucose levels and reduces calorific intake. Any processing can change these relationships by changing the food matrix and therefore how we respond to them physiologically.

This can be a good thing when we cook potatoes or rice as without processing there would be little benefit. Changing the structure of food gives us access to energy. Our brain accounts for about 20% of energy requirements so this was important for our evolution. Cooking is fundamentally a form of changing and creating food structures. But this is not always a good thing.

Excessive processing (e.g., ultra-processed foods) allows us to quickly digest much more carbohydrate and fat than from the same less processed whole food with a matching composition. A study that is often referenced from 1977 neatly demonstrated this. This simple study gave 10 participants test meals that were all based on apples using either a juice, purée, or whole apple.

It transpired that plasma-glucose rose to similar levels after all three meals. However, these levels fell quickly after consuming juice, and to a lesser extent after purée, but not after eating a whole apple. This was because serum-insulin rose rapidly after consuming juice and purée but not after eating apples.

The investigation suggested ‘the removal of fibre from food, and also its physical disruption, resulted in faster and easier ingestion, decreased satiety, and disturbed glucose homoeostasis due to inappropriate insulin release. These effects favour overnutrition and, if often repeated, might lead to diabetes mellitus.’

Dairy products offer us a unique look at the role of food matrices. This is because milk is a complex food that we enjoy in various ways. Cheese is a solid, yogurt a gel or a glass of milk is of course a liquid.

Transforming milk into various products requires processing – such as fermentation, heating and other ripening processes – each of which also transforms the original food matrix. Milk and its associated products are important nutritional food sources for us. It comprises all nine essential amino acids, numerous other vitamins and minerals as well as over 400 types of fatty acids. Yet when we process it into different products they all behave very differently

Investigations have also compared eating butter (who would want to do that?) with eating cheese. They each have the same fat content but eating hard cheese which has a very similar fatty acid composition as butter can cause a much smaller rise in blood cholesterol levels, or no rise at all or even a fall in some cases. This response is because of the physical differences in the matrices of butter and cheese.

The protein in the structure of cheese helps protect the fat from being digested and absorbed; this does not happen with butter. The interaction of nutrients can be significant. Cheese has more calcium than butter; this reacts with fatty acids to form substances that are difficult for us to digest. Calcium, phosphorous and bile acids also combine in a way that can’t be absorbed, which results in the liver drawing cholesterol from the blood, which can reduce blood cholesterol levels.

The food matrix concept is much more complicated than just a set of nutritive values given on our labels. Unfortunately, at present we do not know enough about food matrices to replace our current labelling systems and it is very difficult to build it into diet information.

However, in general, it is a good idea to think about the benefits of eating our food is in its original structure and what influence this might have. Generally, this means eating whole foods or perhaps foods that have been subjected to minimal or only moderate processing.